The History of Kinetic Art

Early Kinetic Art

Kinetic art derives from the Greek word “kinesis”, meaning “movement”. Hence kinetic art refers to forms of art which contain motion. Generally speaking kinetic art works are most commonly three dimensional sculptures that move naturally (eg, wind powered) or are operated via machine or the user.

Kinetic art incorporates a wide variety of styles and techniques, with the earliest examples being canvas based paintings. Kinetic art has its origins in famous artists from the late 19th Century such as Claude Monet, Edouard Manet and Edgar Degas.

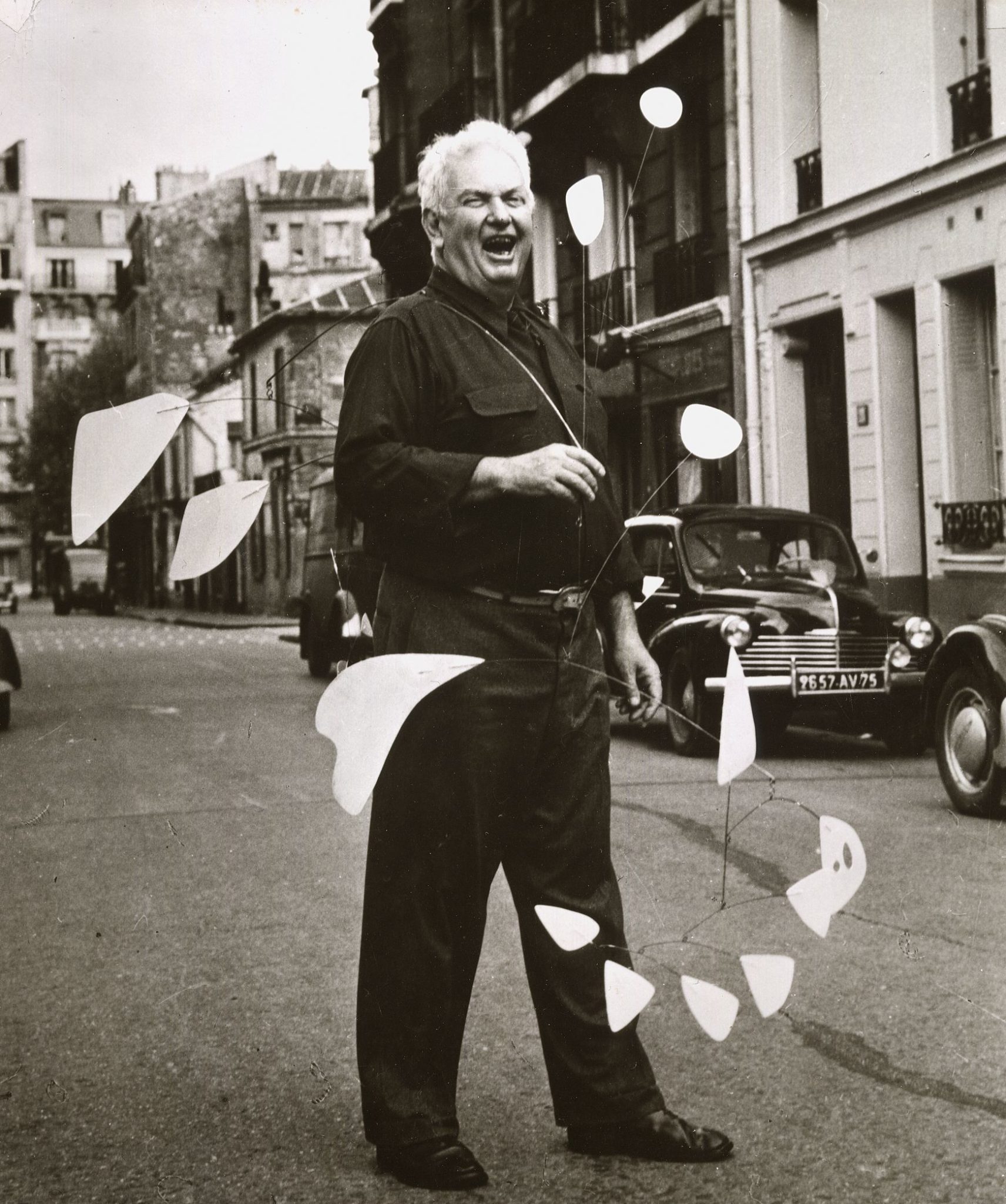

Alexander Calder

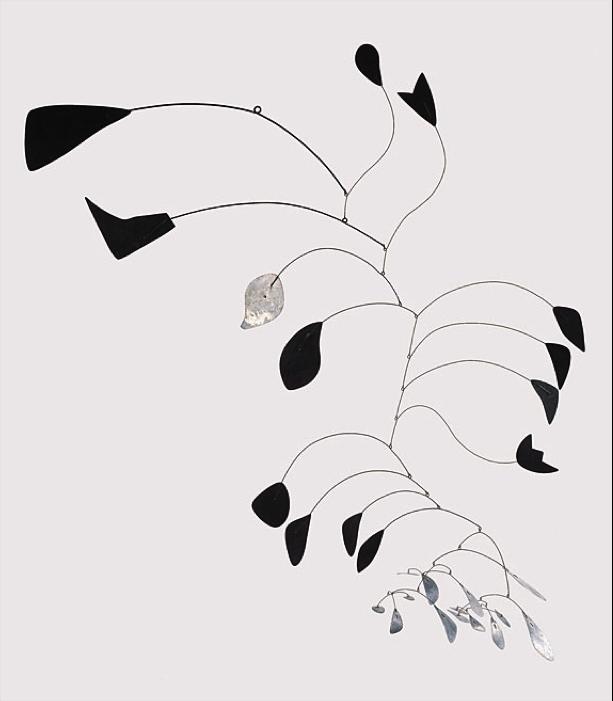

The 1920’s through to the 1960s saw experiments with mobiles and new forms of sculpture, with one of the most prominent figures in the field at the time being Alexander Calder. He was to become the leading exponent of kinetic art for more than 20 years. In 1941 he produced his famous work “Arc of Petals”, which featured naturally created movement as a result of air currents. As Calder put it, kinetic art was striving to “lift the figures and scenery off the page and prove undeniably that art is not rigid”. Kinetic artists utilised mechanical or natural motion to bring about a new relationship between art and technology, inspired heavily by the “Dada” art movement, breaking with conventions of traditional static artwork.

Calder’s “Arc of Petals”

However Calder was not the first to create a mobile sculpture, in fact this was honour was considered to belong to Vladimir Tatlin with his “Contre-Reliefs Liveres Dans L’espace, featuring a series of suspended reliefs. This would be followed in 1920 by Alexander Rodchenko’s “Hanging Construction”. in the 1930’s Calder made the “McCausland Mobile”, a unique piece in that he chose to incorporate shapes that other artists wouldn’t think of using, for example ones that were neither aerodynamic nor malleable.

What Is Dada?

To ensure that he always created a balance mobile, Calder used mathematical relationships to correctly calculate required weights and distances for all of the shapes and pieces involved in his work. By changing his ‘formulas’ he could ensure that all of his mobiles were unique and thus could not be replicated by other artists.

Calder was a particularly important figure in the field as it was his style that essentially created the two types of mobiles that are now referred to as the standard in kinetic art- object mobiles and suspended mobiles, all typically coming in a wide range of shapes and sizes. His central piece in the new style of object mobiles was his 1966 creation “Cat Mobile” (left), which featured a head and tail that were subject to random motion.

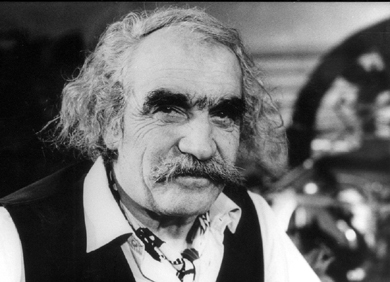

The “Godfather” of Kinetic Art arrives

Without a doubt, kinetic’s art most famous figurehead is Jean Tinguely, a Swiss painter and sculptor who lived from 1925-1991. He created his first piece of kinetic art at the mere age of twelve and he was become famous for using collected items of junk to make his sculptures. His works were known for being whimsical and erratic…..some of them were even designed to self-destruct. Tinguely was fascinated by motion and how it could affect the way object is viewed, hence he loved attached motors to things in order to cause the objects to spin and maybe even be destroyed.

Because his ideas and directions were so different to absolutely every other accepted artist around at the time, it came as no great surprise that Jean Tinguely would quickly come to be seen as a rebel, indeed some expressionist artists went as far as calling him a charlatan. He certainly wasn’t a fan of traditional forms of art such as static easel paintings, leading him to building his own machine- the “Metamatic”- that could paint its own abstract paintings at a rate of up to 20,000 per day!

Tinguely’s “Fata Morgana”

Jean Tinguely

The “Metamatic”

Despite his detractors among artist of the time, Tinguely was immensely popular with the public, who rather ironically actually seemed to be attracted to the fact that his creations were mechanically less than perfect. Some commentators note that the erratic, unpredictable nature of movement of Tinguely’s inventions helped to eliminate the sense of separation between man and machine., Like people, his machines were seen as interesting and amusing rather than cold, mechanised servants.

Tinguely was inspired by Dada and used his work to express anarchic, satirical attitudes towards machines and movement. His 1960 piece “Homage to New York”, for example, ended up destroying itself in a violent performance of sound and light, portraying the wide spread feeling of scepticism towards the values of technology in modern life.

In general at the time kinetic artists formed a profound interest in analogies between machines and human bodies, and used their work to suggest than humans were no more than irrational engines of conflicting lusts and urges.

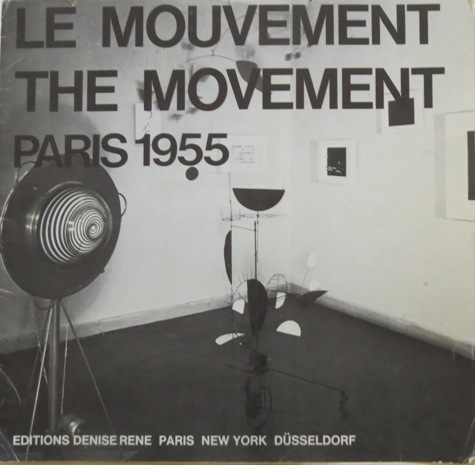

Kinetic Art establishes as a major artistic movement

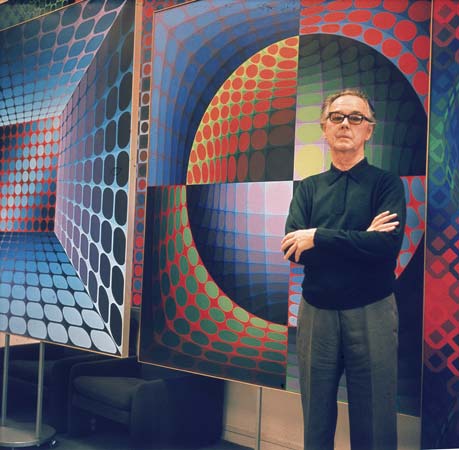

1955’s landmark exhibition in Paris, “Le Mouvement”, is seen by many as the trigger for kinetic art really taking off and being able to attract a wide international following. The exhibition featured newcomers such as Tinguely, as well as Yaacov Agam, Pol Bury, Jesus Soto and Victor Vasarely.

This was followed by the hugely popular “Movement in Art”, a major review of kinetic art in 1961. There were also great successes at the Biennale’s of Venice, Sao Paulo and Paris.

Kinetic art’s ‘golden era’ was deemed to last for around a decade from 1960. However it was not the only emerging art form of the time and it became to be challenged by “Op Art”, led by artists such as Vasarely. This form of art focused on using optical effects and the illusion of movement. “The Responsive Eye” show in 1965 showcased this new form of art and proved immensely popular.

By 1970, there appeared to be four distinctive styles- junk art, popularised by Tinguely; mobile art of which Calder was the pioneer; light-based art, eg, by Laszlo Moholy-Nagy; and illusionistic Op Art.

Op Art in particular quickly gathered momentum and indeed by the late 1960’s kinetic art came to be seen as accepted and stale, a far cry from the radical & anti-establishment feeling provoked by the movement in its earlier days. The fact that kinetic art had settled down into an accepted form discouraged many artists who had orginally been inspired by its avant-garde impetus.

The increasing interest in Op art coupled with kinetic art’s downward trend resulted in an inevitable decline in interest in the movement. By the early 1970’s kinetic art had effectively been abandoned for more digital art forms.

Modern Kinetic Art

Artists have continued to use movement in their work, however today the kinetic art movement appears to be more of a resource for ideas rather than a pressing influence for artists.

Where to find Kinetic Art

Kinetic art can be seen today in several museums and centres around the world, including the following:

– Jean Tinguely Museum – Basle, Switzerland

– Museum of Fine Arts – Houston, USA

– Tate Modern – London, UK

– George Pompidou Centre – Paris, France

– Whitney Museum of American Art – New York, USA

Jean Tinguely Museum, Basle